Turkish leftists, like leftists across the world, were divided over the conflict between China and the Soviet Union. The translated excerpts below are from a report written by the Soviet embassy in Ankara that reflects Soviet fears about Chinese influence in Turkey and proposes methods to counter that influence. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the document is that it demonstrates the Soviet embassy’s sense of the transnational nature of the struggle: Turkish migrant workers in West Germany radicalized by literature from the Chinese embassy in East Germany; Turkish-language Chinese materials distributed by the Albanian embassy in Ankara; and Turkish youths trained in the guerrilla camps of the Palestinian Liberation Organization.

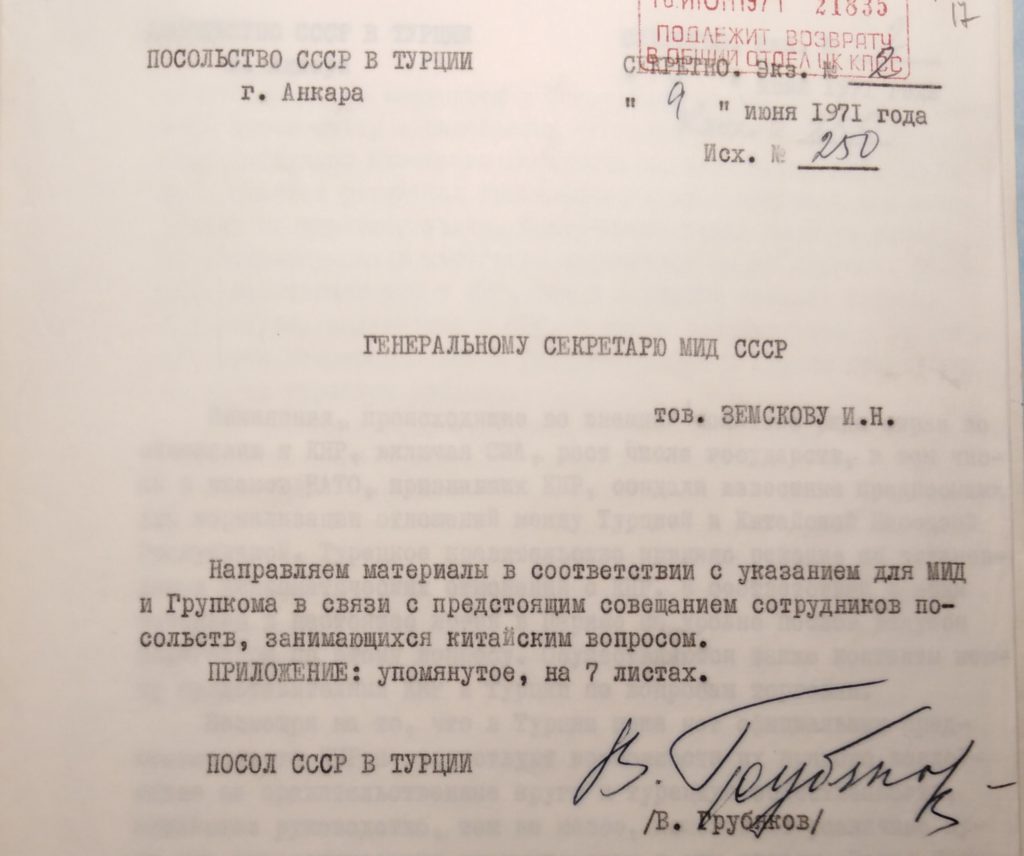

The report was written in the summer of 1971 and forwarded by the Soviet ambassador in Ankara, Vasilii Fedorovich Grubiakov, to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Moscow, as part of preparations for a briefing of Soviet embassies worldwide on approaches to “the Chinese question.” The report’s author, Igor’ Aleksandrovich Lakomskii, was an experienced Soviet diplomat. He was born on 16 October 1918 in Ukraine and graduated from the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ school of diplomacy in 1948. His first major posting was as first secretary to the Soviet Embassy in Turkey in 1955. By the time he wrote the report below he had served in both Turkey and Cyprus; a few years after this report he was appointed Consul General to Yemen. He died on 21 April 2017.

For an academic work that puts this document in context, see Samuel J. Hirst and Onur İşçi, “Smokestacks and Pipelines: Russian-Turkish Relations and the Persistence of Economic Development.”

Embassy of the USSR in Turkey

Ankara

9 June 1971

The changes in a number of countries’ foreign policies towards the People’s Republic of China, including that of the USA, and the increased number of countries that recognize the PRC, among them many NATO members, has created the conditions for the normalization of relations between Turkey and the PRC. Indeed, the Turkish government has taken the decision to develop diplomatic relations with the PRC. Ambassadors from the two countries are, at this moment, conducting negotiations in Paris. Representatives of the PRC and Turkey are also discussing the terms of trade between the two countries.

…

Until recently, one of the most important publications that contained Chinese and pro-Chinese materials was the local newspaper Proleter Devrimci Aydınlık – the mouthpiece of a group of members of the Turkish Workers’ Party led by Doğu Perinçek, someone who had distanced himself from but not broken ties with the party. With the imposition of a state of emergency in May, 1971, the newspaper was closed for an indefinite period. According to our embassy’s information, the group has a press center and a printing house named Kıvılcım in Munich. The press center in Munich receives anti-Soviet Chinese materials in Turkish from the PRC’s embassy in the GDR. The press center works hard to distribute these materials to Turkish workers in West Germany and in other countries in Europe. Some literature published in West Germany enters Turkey through the PRC embassy in the GDR, but mostly it is brought in by Turkish workers.

Perinçek’s group actively works to distribute Chinese propaganda among numerous youth organizations – most prominent among them the federation of Turkish revolutionary youth “Dev-Genç,” where the ideas of Maoism are popular. Members of the federation study the “literary works” of Mao Tse-tung and Lin Biao. A group of soldiers has been created, most of whom have been trained in the camps of the “Palestinian Liberation Organization” in Syria and Iraq. At the moment, roughly 100 Turkish youths, mostly members of Dev-Genç, are being trained in the Palestinians’ guerrilla camps. There is evidence of direct contact between members of Dev-Genç and representatives of Beijing.

Another avenue of Chinese influence in Turkey is the Albanian embassy in Turkey. The embassy spends heavily on the publication and distribution of Chinese propaganda materials in Turkey, among them the embassy’s bulletin. The editorial offices of the Turkish periodical press regularly receive from the Albanian embassy and in the mail informational bulletins from Xinhua, along with Turkish-language summaries of the newspaper Renmin Ribao. English-language copies of China and China Plus are also being distributed.

…

The Embassy believes that the improvement of Soviet-Turkish relations is the most effective tool to counter Chinese propaganda and the activities of Chinese agents in Turkey.

…

Delegate-Advisor of the Soviet Embassy in Turkey

I. Lakomskii

—–

The report can be found in the Russian State Archive of Contemporary History (RGANI), f. 5, op. 63, d. 603, ll. 17-24.

For a recent account of the Sino-Soviet struggle for influence abroad, see Jeremy Friedman’s Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World.

For an analysis of the Turkish left’s interest in Maoism, see Çağdaş Üngör, “China and Turkish Public Opinion during the Cold War: The Case of Cultural Revolution (1966-1969),” in Cangül Örnek and Çağdaş Üngör, Turkey in the Cold War: Ideology and Culture.

– Translation and annotation by Samuel J. Hirst